I spent a lot of years in the military and have worked with many different agencies and countries in that time. One thing I found universally true is the more effective and higher-level a groups (Delta, Special Forces, Navy SEALS, S.A.S, etc, the more they wargame their scenarios and specific missions.

I spent a lot of years in the military and have worked with many different agencies and countries in that time. One thing I found universally true is the more effective and higher-level a groups (Delta, Special Forces, Navy SEALS, S.A.S, etc, the more they wargame their scenarios and specific missions.

These practice run-throughs (drills, exercises, dress rehearsals) includes everything from being generally prepared for possible missions to building mock-up buildings and neighborhoods and using all available intel to make things as realistic as possible. I’m not saying that you need to be prepared for emergencies to that level (this is their job), but I think you do need to use dress rehearsals to flush out vulnerabilities and deficiencies in your plan(s), and the more realistic you make these rehearsals, the better.

According to a 2015 FEMA report, 60% of Americans aren’t practicing for disasters. Pretty much every part of your emergency plan (your family emergency communications plan, bug out route plan, using a ham radio, dealing with medical emergencies, surviving in the woods, dealing with a power outage at home, and many, many other topics, require hands-on training as well as just walking through the plan you currently have so you can update it and try again. The danger is that if you don’t actually walk through the process in a semi-realistic fashion, you won’t realize you’re not prepared until it’s too late. As they say, “Don’t practice until you get it right; practice until you can’t get it wrong.”

Discovering your abilities and shortcomings

One of the biggest mistakes that preppers or others that try to prepare for emergencies or survival situations (and don’t want to call themselves preppers) make is about what they put in their bug out bag. The biggest of the big mistakes is that they put WAY too much in their bag (so they have it just in case) but then when they try to carry it all, they find out there’s no way they could actually use it in an emergency that might require them to walk several miles over various terrains (if they ever bother to put it on and walk around at all). Once you get a bag, throw it on your back and try to use it in the area that you’d actually most likely use it as well as possible areas and scenarios that would be more difficult. You may be surprised. I had been rucking with heavy weights for quite a while in the Army (about 100 pounds with gear, armor and ammo) and was quite used to it. Then when I was spinning up to go to Afghanistan the first time, we spent a few days walking through terrain with large, round river rocks about the size of your fist, and I ended up breaking my foot due to the pressure being placed under the center of my foot. My back, legs and lungs were ready but my feet weren’t.

Discovering problems with your gear

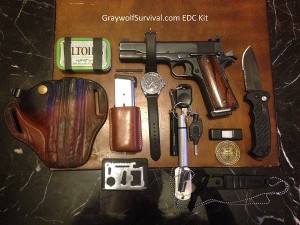

Speaking of gear, I wrote a hugely popular article on how I put together a lightweight bug out bag. It took me a LONG time to figure out what I was going to use because every time I thought I had just the right stuff, I took it all out into the woods and tried it – and found out something just didn’t work well enough. Some things didn’t work as advertised, like these emergency blankets, (I’ve since switched to these), and some seemed like a good idea, such as putting keyrings on the ends of a chainsaw blade for a compact handsaw (The rings not only hurt your fingers too bad, they pull apart after a while. One solution may be to use tougher, smaller rings and loop leather handles through them but I haven’t tried it. I’ve since switched to this Sven Saw, which is definitely bigger but actually works).

Practice does not make perfect; only perfect practice makes perfect

In another example, you can read all day long about how a weapon works, how to shoot like a Navy SEAL, or even specific books on a specific skill such as Single-Person, Close Quarters Battle, but until you actually get out on the range and shoot that weapon, you’re not really preparing yourself. I use this example because it’s easy to understand what I mean about how the realism of preparation can affect your ability to perform when the time comes. Studying and reading books by experts is better than just sitting at home and thinking about things on your own. Going to the range is better than just reading books. Practical shooting exercises with moving targets that shoot back at you (the more they hurt, the better – paintball guns with rubber bullets are better than paintball guns with regular ammo and simunitions training is better than either) is much more effective at telling you where your deficiencies lie. We used to train with a room-sized realistic computerized video simulator with specially-designed weapons that would interact with the system, and if you got hit, there was a tazer attached to your hip that would drop you to your knees. After the first hit, you certainly pay more attention!

Once you get that down, if what you’re preparing for is to defend your house if someone breaks in, run through a plan of how exactly you’d defend yourself if they broke into your house from various entry points, with you in various parts of your house at the time of the break-in. You may find that in one of your scenarios that if they come in through one way and you’re in the living room or kitchen, that you may be cut off from whatever your weapon is that you were going to use, thereby requiring you to go to plan B. Do you have a plan B? You may either need to have a secondary weapon that may buy you time available (which could be either a secondary firearm, chef’s knife, or even an ornamental samurai sword – don’t laugh, it could be better than grabbing a lamp. I actually have one of these swords in my living room), or work on some other plan.

Suggestions on wargaming

In preparing for emergencies, the best way to do it is to look at what situation may happen and what you’re going to do about it, and then try to come up with a way to duplicate that situation as closely as possible. Here are some examples:

- Extended power outage – most people plan on a power outage happening for a few hours, so they just buy flashlights and emergency candles to keep around the house. In the case of earthquakes, hurricanes, floods, or even perhaps an EMP or other regional occurrence, your power may be out for much longer. Do you know how that would really affect you? Try actually shutting off the power to your home for longer and longer times. I’ll be that you’ll start seeing problems that you never thought of, such as what to do with the food in your fridge/freezer or how you’ll keep your home warm/cold – or even cook with out power. You won’t really know until you actually try it.

- Getting a hold of your family in an emergency when cell towers are down – as of this writing, pretty much no one in Puerto Rico can use their cellphone to call anyone due to Hurricane Maria. What would you do if this happened? One thing you’ll want to do in your emergency family communications plan is to practice. Decide on some trigger (something mentioned on the news, your designated communications person deciding it’s so – whatever you can think of that won’t allow people to try to game the game), and then time how long it takes to reach every person in your group without using cell phones or the internet. There are many scenarios that you might think of to do this that will require different planning, such as what to do if some or all of you are out of town, if one person has an emergency that the others need to know about, or if the whole area is affected. Just think it through, come up with a plan to wargame this scenario, and try it.

- Try to use and test all your gear when possible – If you have a good supply of emergency food stocked in case of emergencies, make sure you actually use it. The stuff may last for years but not forever, and it would be nice if you knew how to make decent recipes with what you have or know what seasonings or other food to get beforehand as well as how to cook it all. Make sure you also use all the gear you’ve stashed in your emergency go bag or at your home so you know how to use it all and that it all works. The last thing you need is to be in the middle of a disaster and find out you don’t actually know how to reach someone on your ham radio (which is why you need a ham radio license, no matter what the guys on the forums might tell you).

- Forced or voluntary evacuation – If something happened where you HAD to leave your home (fire, flood, martial law, impending hurricane, etc), would you be ready? What if you had 5 days to leave? What if it was only 5 hours, 5 minutes or 5 seconds? Do you have all your important items (and people) ready to do that? Practice emergency drills to see if you are by having a designated person declare at random that an emergency has just happened and have them explain the the details as they know them at that time, and how long everyone has to evacuate to X. X could be a mile down the road, a family member’s house, or whatever. This planning is intimately connected to your commo plan.

- Practicing for wilderness survival – Camping is pretty much the best way to do that in most cases. Just make sure that if you’re using camping as a way to teach your family or group about survival that you don’t forget to make it enjoyable and rewarding. Give assignments to each person to teach some aspect of survival (I’d suggest working with them before they present, so they not only teach the right thing, don’t feel like an idiot because they incorrectly prepared).

- Don’t rely solely on the experienced members – As much as possible, try to get younger or less experienced members to have to solve problems without having the leaders give them instruction. If they’re stuck having to deal with something on their own (many people get separated from their family members during hurricanes), they need to have some basic understanding of what to do without having someone tell them what to do.

- Look at things from the outside – The main thrust of my job as a counterintelligence agent was to protect our forces from what the enemy can see or do. One way we would do this is by creating a Red Team that would be the enemy (also called OPFOR in tactical training). The Army defines red teaming as “structured, iterative process executed by trained, educated and practiced team members that provides commanders an independent capability to continuously challenge plans, operations, concepts, organizations and capabilities in the context of the operational environment and from our partners’ and adversaries’ perspectives.” Our group would try to infiltrate or observe an organization or facility or try to gather intelligence from personnel or equipment to see how good their OPSEC and processes were. Look at how other people might affect your plans if they wanted to do it and have someone pretend to be them during your exercise, and then have a debriefing afterward with everyone to discuss what each person observed and what you could improve.

- Mid-exercise complications – Once you think your group is doing ok with a training exercise, have the designated training person (whatever you want to call them) call out some possible complication and see how everyone deals with it. For example:

- If you find one person has been carrying the majority of the gear, declare that they’ve now broken their leg (could they deal with the leg and then the gear?).

- If someone has made a decision to do something that you see could be a potential problem, such as taking a shortcut to an area while the rest of the group continues the correct way, declare that cell service is down for the area and you just got a flat tire (Do you have the tools and experience in the car to fix the flat tire? What will the other group do once they arrive and find themselves alone?).

- If you’re practicing a bug out route to get to a family member’s house or just out of town (designate a destination), declare that a tree has fallen in the road or traffic is backed up for the next 50 miles, or the road is flooded, and you can’t use the main road. How would you get there now?

- If you’re camping, declare that your primary and secondary methods of starting a fire are missing (stolen, lost, whatever). How would they start a fire then, assuming there were no campers around to help?

- Make your training useful but enjoyable – If you want people to actually want to do this sort of training, make sure they like doing it. Assign each person a particular primary job in each plan (but have backups). Have them teach something to the group about their job (first aid, using a radio, filtering water, starting a fire). Getting people involved is very effective in getting buy-in from people. Make sure that people (including you) aren’t getting stressed out during your training exercises. Remember, this should be something you should be continually doing and not just a short-term thing.

I am just a beginner and am an old man, single+ alone. I have been checking out different sites, so far yours is thebest so far. thanks for your effort.

For a start, with 3 kids I had to make it fun in the backyard. With an imminent ice storm I grabbed my B.O.B. and set up a shelter. I learned some things and satisfaction with others. Always improving packing techniques, applications, inventory bag. Build up to a real emergency. Thanks for your posts.