There are tons and tons of articles on the web about what you should cache, what they should go in, and how to place them. What I don’t see very often is much that explains how to plan and select cache sites and how to properly document them so the intended person can retrieve them. This article is an extension of the article I wrote on How to document your bug out route or cache locations but more specifically geared to planning and documenting locations.

There are tons and tons of articles on the web about what you should cache, what they should go in, and how to place them. What I don’t see very often is much that explains how to plan and select cache sites and how to properly document them so the intended person can retrieve them. This article is an extension of the article I wrote on How to document your bug out route or cache locations but more specifically geared to planning and documenting locations.

Placing equipment, supplies, documents and money in advance of an operation or as a contingency plan in case things go wrong has been an important part of military and espionage operations ever since people started planning operations. Properly placed and retrieved items can help resupply local troops clandestinely, extend an operation in an area, or assist in personnel evacuation. Special Forces, rebel groups and intelligence agencies all do this.

Even if your plan is to disappear from the digital grid, having a proper cache plan is essential.

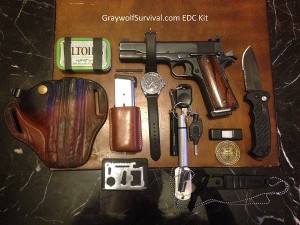

If you’re a prepper, you should be considering a cache plan. You never know where you’re going to be when SHTF or something happens that you need to leave town. That means that if you have to leave right now, you’ll only have what you bring with you and what you can find along the way. That’s the beauty of a cache: it’s a pre-staged resupply point. Whether you’re trying to hide your guns and ammo from thieves, bandits or an oppressive or occupying government or just have things in place to recover from a disaster, having pre-placed supplies can mean the difference between surviving or being a statistic.

So why would you really need to consider taking all the time and money to hide extra supplies that you may never use? Let’s look at a few scenarios. Some are more likely than others and some are just to put you in the mindset of how caches can and have been used:

- You live in an area that has occasional flooding, tornados, earthquakes, or hurricanes. If something happened that either wiped out your home or required the area be placed off-limits while you were out, you wouldn’t be able to get home to grab anything. Hopefully you at least have a bug out bag that you’ve planned and packed with what you need with you but that and what’s in your car (if you have your car) will be it. If you had items placed outside of town, you could just head that way and pick up what you needed.

- You’re living in a foreign country that has a history of rebellions and coups. In these countries, it’s sometimes necessary to di-di-mau ricky-tick (pronounced deedeemoww rikeetick: leave quickly). Items like fuel and water aren’t always available. If you have food, water, and fuel staged in a couple of places, you can just pick them up along the way to the embassy or the border.

- Let’s say society collapses and you need to head out to your idillic cabin in the woods 500 miles away. Unfortunately, gas stations are all closed and grocery stores are empty – and it happens while you were visiting your loony Aunt Becky upstate so you can’t go home. Luckily you’ve pre-placed some fuel and clothing along your route so that when you head out, you’ll be able to get to this stuff and continue on your way.

- Society has gone to shit and there are riots or roving bands of thugs everywhere. This could be due to any number of reasons such as a large natural event or long-term SHTF scenario. A large group of ne’er-do-wells comes along and evicts you from your home and they take all your stuff. What they didn’t know is that your group can now just head out to a few cache locations, grab food, water, and weapons. Time to commence with Operation Gimmemyshitback.

- You find yourself in the near future where your country, or the country you happen to be living in, is taken over by people who aren’t very nice. A resistance group has grown to fight the oppressors but you can’t join them without risking everything. They are running out of supplies but you have plenty of access. By placing items in cache locations, you can help support them without ever being caught with them. You eventually take back the country and a popular massage parlor is named in your honor.

Because caching operations are more advanced than typical prepper activities, the situations you’re trying to deal with will sometimes be a bit more advanced, and in some cases, less likely. Since you don’t really know what situation you’ll be facing, you kind of need to plan for the worst and hope for the best. If you’ve planned and executed your caching activities with the mindset of a rebel that’s found himself up against a hostile government, then you shouldn’t have any problem with something like staging supplies to help when a storm blows through your town and flattens half the buildings. So that’s how I’m gonna write this up.

There are some essential elements of a successful caching operation:

- Items must be located in an area that the intended recipient (and the person placing them) can get to

- Your intended recipient must be able to locate the cache without an extensive search

- Unintended recipients (the enemy) must not see you place the items or know you’ve placed them

- The enemy must not find your items

- The items must be placed to the intended recipients don’t get caught retrieving them

- Items must be protected from the elements or damage while cached

- If items are found by the enemy, the cache location or items must not give away who placed them or who was to retrieve them

So how do you go about doing this? First of all, hopefully you’ve sat down and figured out just why you’re prepping in the first place so you know which scenarios you’re expecting and which risks you’re trying to mitigate. With that information, you need to walk through some thought exercises about where you’d go and what you’d need to have with you. Anything you don’t have with you, you’ll need to find somewhere or place to be found. This is the stuff you should consider caching. I can’t really help you with that part.

Once you have an idea of what you need to place, now you need to know where to put it.

Map surveys

The first thing you should do is a map survey. Pull out a map of the overall area that you’ll be in that covers both where you’ll be starting from and where you’ll be ending up at if it’s for a route. Take a look at all the major roads, minor roads, waterways, and places that you should be able to easily identify onsite such as mountaintops or water towers.

You want to identify places on the map that you DON’T want to use as well as those that you might. If you’re considering rural resupply caches, you don’t want to place them near high traffic areas, populated areas, or in the middle of a field because it would be difficult to conceal their placement or recovery. If you’re considering that you may be working in occupied territory, you’ll want to avoid locations of military significance such as factories or bridges, as well as tactical points such as choke points and natural funnels that may be frequented or manned by hostile forces.

With that information, you should be able to start locating tentative locations for caches. Keep in mind that you’ll need some kind of concealment for your routes in and out of the location as well as the location itself. Try to ensure that you have good alternative routes in and out of the locations as well.

From those locations, see identify the reference points on the map that the intended recipient would be able to use to find the general area. A bend in the river, halfway point between two tall hills, southern-most tip of a lake, etc. These locations should be unique and easy to know that you have the right one. Using something like the fork in a trail may not be the best choice because trails are a lot more difficult to identify than you might think. If you’ve ever done land navigation in a dense wooded area with logging trails, you know that trails are poorly marked and recorded and look alike. You could easily be on the wrong road or be caught by a roving patrol or gaggle of hooligans.

If you’re operating in an urban environment, the same principles apply – they’re just different.

Recon

Once you’ve identified your possible locations, you need to check them out in person. If you’re currently concerned about your OPSEC (and you probably should be), you shouldn’t plant your caches during your reconnaissance. Just go to each place and see the truth on the ground.

You’ll want to bring a GPS, a good compass

, maps of the area, notepad

and pen

, camera (cell phone camera would work), and long measuring tape or rope. You should also bring a metal probe that you can shove into the ground if you’ll be digging so you know if you actually can dig there.

Before you go, come up with a reasonable explanation as to why you’re there and dress/equip accordingly. If you’re bird-watching, you may want to bring a pair of binoculars and a book about bird watching

, for example. Unless you’re operating in occupied territory, you probably won’t be searched but consider some explanation for each piece of gear you have even if it’s just that you use it for other things but keep it in your pack all the time.

Depending on how much time you have and how concerned you are with OPSEC, you may want to do your recon in a couple of stages. Identify and rule out areas and then return to re-visit and mark specific locations with specifics. Keep in mind that the more you visit an area, the more likely it is that someone will notice. You may decide to just mark the locations fully as you come across them. That would save time and be more secure but means you may miss better locations.

Keep in mind that if you think it’s a good place for a cache, someone else may as well. Digging a hole may be fairly safe but it takes time and is easy to lose if you’re not thorough. Placing things up high in trees or in abandoned buildings may work pretty well. Also, consider putting things under water if you have the right container.

First, canvass several areas and rule out ones that won’t work while identifying places that would that you couldn’t see from your map survey. Once you’re done, go back to the map and decide which locations are to be used. Then return to the locations and document everything about it. Keep in mind that even if you’re placing these caches for yourself, it’s probably more difficult than you think to find a spot again. Also, your plans may change and you may end up sending someone else to either place or recover the cache that you weren’t considering before.

Take the time to do a thorough job. Areas look different at night than they do in the daytime. An area scouted in the winter when all the leaves have fallen looks completely different in the summer. Due to operational changes, you may have to enter an area from a different direction than you did when you surveyed it (which you should do anyway).

The makings of a good cache site

So what is a good cache site anyway? In addition to the tactical considerations, you need to have a couple of good reference points. The first should get you within site of the cache site. The second (the final reference point) should either mark the location directly or be easily paced off or measured from that point in a known direction to exactly where your cache is located.

The first point should:

- Be easy to locate and identify from your route

- Be something that can be identified regardless of season or time of day

- Be very simple to explain what it is and how to find it. The last thing you want is to document some hill and then see a hill that fits the exact same description but it’s the wrong one.

- Be a location that you can use to easily find the final reference point. If you use the top of a mountain for example, you may need some intermediate reference points to narrow down the area.

Preferably, this should be a location you can actually stand at and head out from to get to your cache site.

Once you’ve decided on a cache site, you now need to find the exact spot of the cache. You do this by identifying a final reference point that your first point directed you to. This point should:

- Be easy to identify that you’re on target. You need to find something right at the precise location that is easy to identify when you’re standing in the cache site.

- Be marked by something that doesn’t change or move. The bend in a river is a good location to mark a general area but flooding and seasonal change can move it so it’s not good for this.

- Be easy to be directed to from your other reference point(s) with a simple description.

- Be close enough to the cache to easily measure. The final reference point may be directly at the cache to make it simple but that may not be possible.

- Be permanent. If you mark a location with a tree branch, the first windstorm that comes by will hide your stuff forever.

You don’t have to just have one thing as your final reference point. You could use something like the halfway point between the corner of a fence and a large tree or site along two trees to give you a line and measure out 30 feet to a row of bushes where you bury it. In any case, take an azimuth with your compass as a backup. Remember though that if you rely on a compass only to mark the direction, you may not have a compass when you come back to get your stuff. That goes double for a GPS.

Document your cache location

As you find locations that you want to use later, you need to document them so you can come back later to place them. Depending on your circumstances, you may just place your cache the first time out but that means you have to bring your stuff with you as you traipse through the woods. A best practice could be to identify the area in the daytime and place the cache under the cover of darkness some time later, especially by someone that didn’t do the survey.

Once you’ve identified the precise location, and then again once you’ve actually placed the cache, you need to do some writing.

Sketches

The first thing you should do is make a couple of sketches. The first sketch should be a large overview of the area that includes your likely routes in/out, all your reference points, and your cache site. The more detail, the better. The second sketch should be of the cache site itself and should include the final reference point, the cache location, and anything else within view that would help orient you in the area. Your measurements and azimuths should all be on the map as well as written directions.

You should provide enough detail that you could just hand these two sketches to someone and they could head out to the area and find your cache. What you should not do (if possible) is put anything on the sketches that give up exactly where that area is. For example, you wouldn’t want to identify a particular highway and mile marker on the map. If someone gets a hold of your sketches that you didn’t intend, you don’t want to send them to your stuff. Your reference points should be easy to identify if you know the area you’re going, without giving up the area to someone without that information.

Photos

You should take photos of the exact location of the cache, taken from different directions. Each photo should have a description such as the direction you were facing and the distance to the cache from the camera. Also, take photos from the cache location (if possible) facing north, south, east and west. If you identify something in your map or instructions, try to take a photo of it.

Written instructions

You may not be able to give a sketches to someone. You may have to relay instructions by phone or radio or send an email. Whatever. You should be able to explain how to get there in very specific directions. Include as much information as possible that you or someone else may need to know. Regardless, this detailed wording helps out tremendously if you’re using a sketch anyway. Write it out so that you could read it to someone and they’d be able to find it with nothing else.

You should include the following with your written instructions:

- An inventory and/or description of the contents, including size and weight

- A description of how it’s cached (buried, sunk, placed in a wall, under floorboards, etc)

- Description of the general area including the type of terrain and any pertinents such as who’s in the area or whatever

- Description of the immediate area to include things that might not be necessary to find the cache such as water sources or places that can be seen from the road

- The date the item was cached

- Details of how it was cached (how deep, in what container, etc)

Things to do after placing your cache

Once you’re done hiding your cache, you need to sterilize the site as much as possible. If you dug a hole, it’ll be obvious until nature takes over so if you haven’t chosen a site that has its own natural cover such as inside a group of bushes, you might want to throw some leaves or something over it in the meantime. Clean up all your footprints and make sure you haven’t left anything like cigarettes or gum wrappers around.

Once you’re done, you should send someone out to find the site to verify your instructions/sketches etc. This person should not be someone who was involved with recon or placing the cache. They should come back with notes that should be included in the final instructions and also try to improve the site’s sterilization.

Other considerations

If there’s a possibility of your location being discovered, you might consider some form of distraction. You could bury your item deep, cover it up with dirt, and then bury a decoy cache above that. It’s the same idea as carrying a wallet with a few bucks and some canceled credit cards in case you get mugged. If they’re looking for something, they may stop looking once they find something.

Items that expire

If items have an expiration, mark that in your instructions. You may need to restock your cache on occasion. If you’re placing fuel somewhere, make sure you put in a fuel stabilizer or maybe also a fuel antifreeze. If you’re placing something like water inn a location that could freeze, make sure you leave room for expansion.

Changes in magnetic north

The poles in the Earth move all the time. As such, magnetic North changes over time. You should mark down the current declination of your area when it’s documented. If the declination changes between then and when you have to go back, you could just adjust for the new direction. This shouldn’t make much difference in a short distance but if you”re orienting to a point off in the distance, you may be off by quite a bit. Having more than one azimuth point in different directions would be very helpful.

Placing a cache at a residence or workplace

In some cases, you may want to place a cache right in your home. If you have something extremely valuable that you need to get, you may decide to put a cache location right in your home. Hiding things at your crib is a balance of ease-of-access vs ease-of-discovery. In a lot of cases, if it’s easy to get to, it’s easy to find. Stashing a load of silver or gold coins in a drawer would make them easy to grab if you needed them quickly but a thief or a hostile search would easily find them. Putting them in a wall and then having a trusted construction dude cover the hole would make it almost impossible to find but you’d have to destroy your wall to get to it.

Of course, this goes for placing them in a location other than your home, such as the home or office of a friend. If you’re placing items to be picked up by someone else and you don’t want anyone to know your relationship with that person, placing items in your home or office – or that of one of your family – isn’t going to work. They’d give away your relationship if they got caught there. Same goes if you place something in their home or office.

Speak Your Mind